John Simmons remembers the first time his friend, Bobby Sengstacke of the Chicago Defender, let him borrow a camera. They went to a convention in the sixties and Simmons said, “I shot a few pictures and a couple of them he was really impressed with when he processed them. He said, ‘Man, you got an eye.’ And that was the beginning.”

Simmons took to the Chicago streets taking pictures of the life he was experiencing. Because it was very segregated at the time, he spent all of his time within the African American community and his photographs reflect the experience that he was embracing.

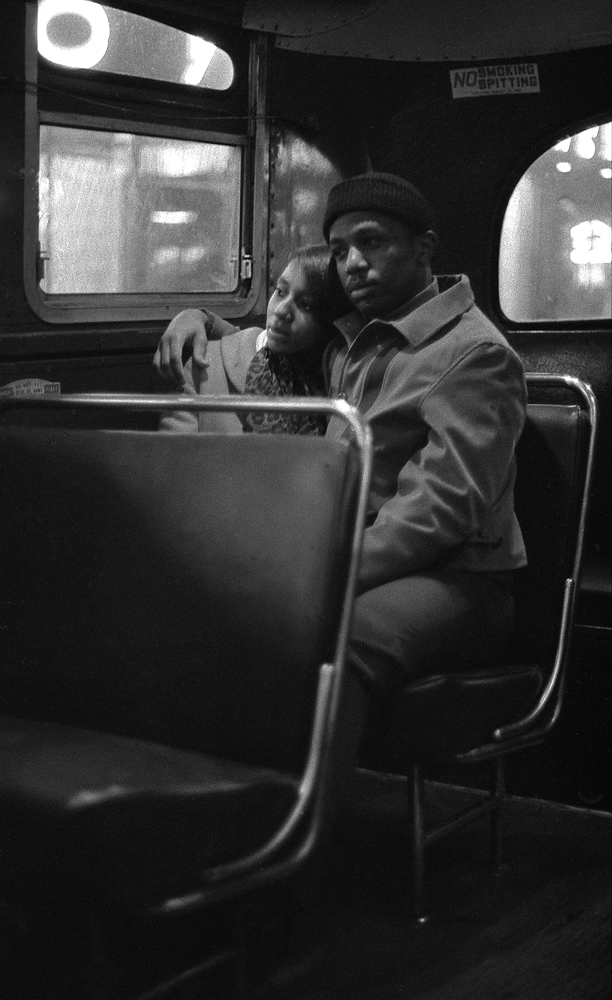

Love on the bus 1967 Chicago

“So dig it – later on, something else began to happen. I began to realize that I was actually telling a story and it filled in a lot of places. It took the place of music, it took the place of poetry, it took the place of painting. It was an art form that I was able to be fluent with, I was able to be intuitive with.”

Men talking in doorways, a couple sharing a moment on a bus ride, children in windows of apartment buildings, Simmons captures these fleeting moments and the viewer experiences the closeness between the photographer and his subject.

“I didn’t take many pictures you know, at that time, because you had thirty-six exposures. It wasn’t like you could shoot five hundred pictures on a digital camera. You had thirty-six exposures and maybe a roll of film in your bag or pocket. You were very decisive as to what you used the shutter on.”

Man With A Pistol , Chicago 1965

There was something about people and candid street photography that Simmons was drawn to. “I felt like me and my subjects were meant to be together. We were meant to have that crossing because they allowed me to tell that story, they allowed to meet me at this place. Later on, I began to feel that we’re always the sum total of our experiences, every moment, we never come to a stop. We’re in a continual state of becoming. To be able to take a photograph and see something in a certain way is a product of who we are. It’s not only a product of who we are, it’s a product of who our subject is at that moment. I think that that in itself is just so amazing.”

Taking Aim 1971 Nashville,TN

Simmons lives by his words and is in a continual state of becoming, especially when it comes to his work. After the loss of a close friend, he went home to his studio and saw a photograph of the Black Panthers and realized no one had seen it, ever. He thought, “If I don’t start printing, I’m going to be Vivian Maier, they’re gonna be finding my stuff later!” After that, he printed and framed over a hundred and twenty photographs and dedicates his Saturdays to going through his archives and making prints.

For the first time since the seventies, his work is being shown across the country and gaining recognition from prominent institutions. One day, he got a call from a curator at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for Visual Arts asking to include his work in their show on James Baldwin’s America. Simmons was blown away. Not only was Harvard a very prestigious place for his photographs to go and live, but they were being shown alongside everyone he’s admired throughout his entire interest in photography such as Diane Arbus, Roy DeCarava, and Robert Frank. Along with those prints entering Harvard’s permanent collection, six prints have gone to the High Museum in Atlanta, one to the Houston Museum of Fine Art and another to the Cochran Foundation. Simmons doesn’t know what happens next as his prints begin to take on a new life. He had always made his work financially accessible for people, but now it is being shown with photographs that very few people can buy.

What’s important to him is that people are seeing his photographs and remembering that experience. While a photograph captures a moment in time, the print represents eternity.

Window writing Chicago 1968

“Somebody looks at that picture and somebody is moved by that picture and they’re changed by that picture. And because they become a different person because of having that experience, the moment they’ve gained they pass on to another and that becomes a new thing that begins to live on its own.”

He recalls a time he walked into a gallery in a business district that was showing his work. The gallery was empty except for himself, the owner of the gallery, and a woman dressed in a suit. Upon hearing that he was the photographer, the woman approached him explaining that she had just purchased his photograph of the two shoes. Her eyes began to well up as she spoke about the photograph, telling John of the fortunate life she had lived. When she saw the photograph, it reminded her of everything that she had to be grateful for. She planned to hang it next to her front door so it was the last thing she saw as she left each morning. That photograph would serve as a reminder to appreciate everything she saw that much more.

Will on Chevy 1971 Nashville

John finished the story with “And I have to tell you, that blew me away. It’s exactly what I’m talking about in terms of that woman was affected in a way and changed by a picture. In a way that I’m sure she’s going to take it into other situations. So I think that in certain cases, the photograph is all about time and the print is all about eternity, it lives. That’s how I’m feelin’ these days.”

When asked about his favorite camera, Simmons laughs and says, “God, I have a problem with cameras. I feel like I need a twelve step program.” He grew up shooting with Nikon and Leica, and then went digital with a Sony A7R3. Though it’s important to note that the Sony has a Leica lens on it that Simmons bought in the sixties. The camera that he’s “completely in love with” and uses most often is “a little Lumix LX100C that just fits in my pocket – it won’t fit in my pants pocket but it’ll fit in my jacket pocket.”